The night before I was to meet the poet Maggie Smith, I woke myself up from a dream by clawing at my own head with my fingernails. In the dream I was defending my family from a zombie attack, and we were holed up in an abandoned church, as you do, and I’d managed to hide my kids up in the choir loft before the howling undead battered down the doors, and as I was grappling with one red-spattered monster my youngest daughter appeared at the bottom of the stairs, and when she said “Daddy?” that’s when I scratched myself awake.

My phone told me it was 3:22 a.m. That evening I’d flown to Columbus, Ohio, where Smith lives, on a packed plane in which everyone sitting around me was coughing behind their ill-fitting masks, except for the guy in the TRUMP 2020 mask who muttered darkly. In my pitch-black hotel room I relived the final moments of the dream, then yanked my mind away as you yank your hand away from a hot pan. I thought, instead, of the hopeless real world. Ruth Bader Ginsburg had just died. Louisville, Kentucky was not going to file any real charges against the officers who killed Breonna Taylor. The West was burning, and the plague was spreading.

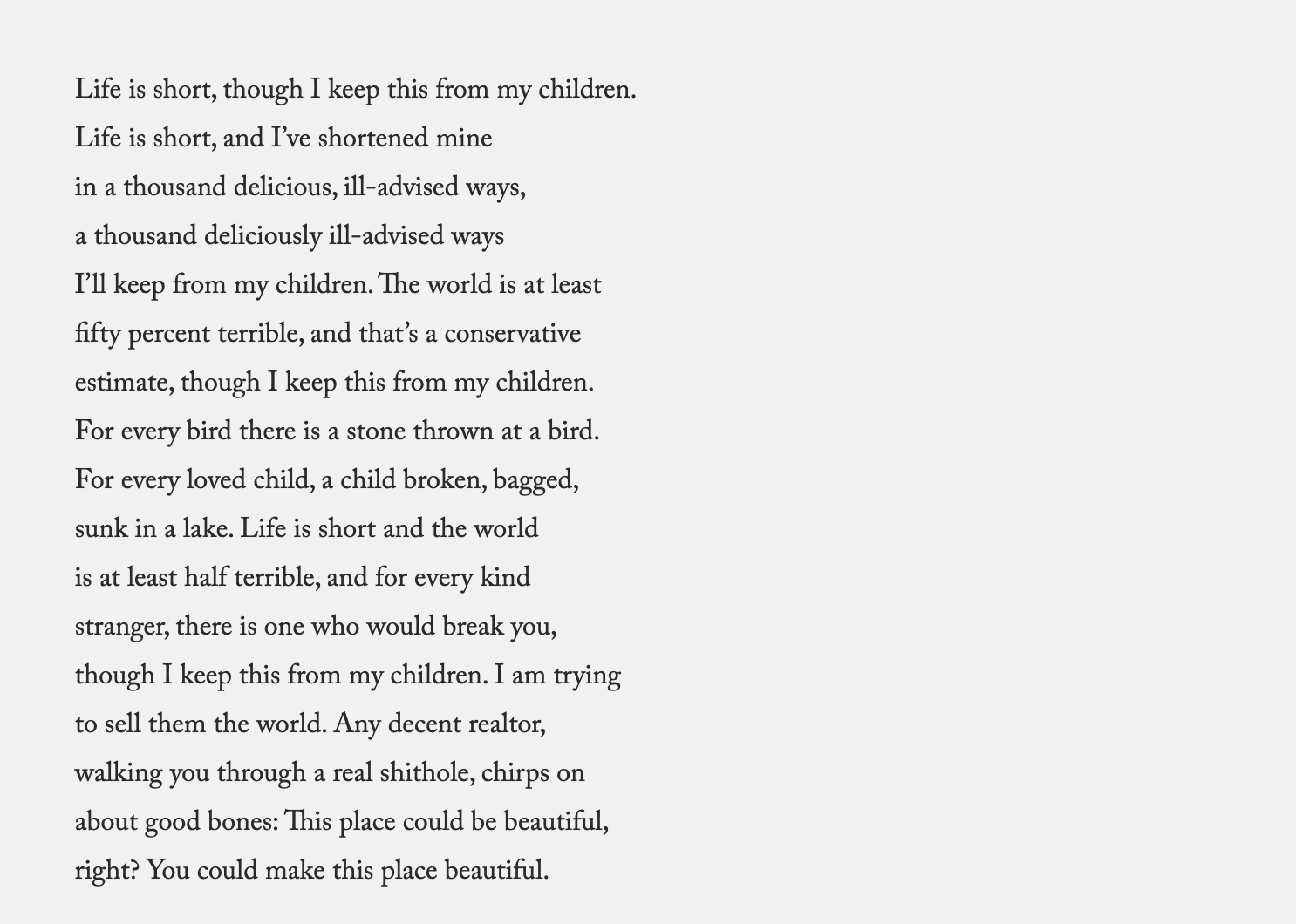

In the summer of 2016, in the wake of another horrifying real-world event, the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida, a poem began spreading all over social media, shared by your mother-in-law, your most artsy college classmate, Megan Mullally, and maybe you, too. The poem was called “Good Bones,” and it elegantly, wittily distilled a very particular feeling of being afraid about the world and daunted by the challenge of raising kids in it. “Life is short,” the poem begins, “though I keep this from my children.”

As bad thing after bad thing kept happening that bad year, the poem became a kind of litany on my social media feed, a mantra of hope in hard times. Smith, previously a little-known (even for poets) poet who lived in Ohio and had published her collections with tiny independent presses, was featured in the Washington Post, on Slate, on PRI, which called “Good Bones” “the official poem of 2016.”

Shortly after this flurry of attention, Smith’s marriage fell apart. Near the end of 2018, that bad year, she started posting daily encouragements and affirmations on Twitter. “Today’s goal: Stop rewinding and replaying the past,” she wrote in one representative tweet. “Live here, now. Give the present the gift of your full attention.” She ended that tweet with the same two words that ended all the tweets, clearly a message for herself as well as for her then-16,000 followers: “Keep moving.” Now, in 2020, the worst year yet, comes Smith’s commercial debut: not a collection of poems but a quirky quasi-memoir called Keep Moving, which intersperses those affirming tweets with personal reflections on the hardest days of Smith’s life and features blurbs from the inspirational blogger Glennon Doyle and the singer Amanda Palmer. Four years after “Good Bones” went viral, in the midst of an even grimmer moment in American history, this new book feels like a clear bid to transform Maggie Smith from a famous (for a poet) poet into a guru of literary self-help.

The morning after my dream, I drove to Westerville, Ohio, the Columbus suburb where Smith grew up, and met Smith at the front gate of a public garden. It was a perfect September day and I wore a baseball cap to protect my scalp from the sun, and also to cover the scratches on my head.

“I used to bring my kids here all the time when they were little,” Smith said. We walked by a fountain where, Smith recalled, she’d attended a Girl Scout event with her daughter during which another girl had leaned too far over and fallen face-first into the water. “Just splashed down in there,” she said.

Smith is small, with a pixie haircut grown shaggy in quarantine—“mutton chops,” she said despondently. She carried a tote bag covered in drawings of upraised middle fingers. In person, Smith has the air of a friend who’s confiding secrets. When I asked if all the nature imagery in her poetry meant she was an outdoorsy type, she pointed to her shoes, simple ballet flats with a camouflage pattern. “Don’t tell anyone,” she said, “but I’m a walker, not a hiker. I won’t go anywhere I can’t walk in these shoes.”

In Keep Moving, Smith writes about being a fearful child, wary of surprises: “I thought of change as some interruption in my life, a veering off course.” Sitting on a bench by that same fountain, Smith elaborated on this fearfulness. “Needing to know what was gonna happen next was a big thing for me,” she said. She was a list-maker—her grandmother’s family nickname was Checky Listy, and young Maggie became known as Little Checky Listy—and she recalled writing a detailed order of operations for Christmas morning:

1. Get dressed

2. Drive to Grandma’s

3. Have a Shirley Temple

4. Open our presents

5. Play with our presents

“Who has to make a list that has ‘play’ on it?” she said ruefully.

Other than a year spent teaching in Pennsylvania, Smith has never lived away from the Columbus area: college at Ohio Wesleyan where she met her future husband, a post-collegiate year working at the car dealership where her mother ran the finances, an MFA at Ohio State, marriage and two children just a few suburbs away. In her first year in graduate school, Smith was thrown to learn she would have to take a bus to campus—in fact, would have to transfer buses. Before classes started she made the boyfriend she was soon to marry take her on a practice run. He showed her where to feed her dollar into the fare machine, and how to take the paper transfer ticket out, and when to pull the cord for your stop. “Like you do with a kindergartner,” she said. “I was 22 years old.”

But over time, Smith and her husband, an attorney, built a life that resembled her childhood, steady and secure. “To me that’s the ideal,” she said. “When your kids know what’s coming.” And then, over the past four years, it all changed. “Everything got thrown up in the air and then sifted back down into different piles,” she said. “I had to let go of my lists.”

Smith wrote “Good Bones” in a Starbucks around the corner from her house on a weeknight after her husband got home from work. Unusually for her, she composed the poem in one go rather than labor over it for days or even months. It appeared in the literary journal Waxwing in June 2016, the same week as the Pulse shooting, alongside two of her other poems.

Rereading “Good Bones,” it’s surprising how ambivalent the poem seems to be about the hope it’s offering the reader. (Smith says she sees a lot of debate online about whether the poem is a downer or not.) There’s mischief in the poem—the “thousand deliciously ill-advised ways” Smith has shortened her life, which “I’ll keep from my children.” But it’s also glum, in its litany of horrors: strangers who will break you, birds struck by stones. “The poem makes plausible the idea that we’re not fucked,” says the critic Stephanie Burt, “while acknowledging that sometimes it’s hard to believe. In that sense it is what Auden said all the best poetry was: a clear expression of mixed feelings.”

Speaking as someone who spends a lot of time trying to make things become popular on the internet, I can say that ambiguity is not usually a recipe for viral success. In my experience, viral success is typically closely connected to a simple, direct point of view, expressed loudly. But the success of “Good Bones”—as well as the previous poem to go viral in this way, Patricia Lockwood’s “Rape Joke”—suggests people share poetry for different reasons than they share other kinds of content online.

“Whenever I see people share poems,” says the poet and nonfiction writer Hanif Abdurraqib, who lives in Columbus, “I wonder if they have found the language they were reaching for but couldn’t access.” I think that’s right about “Good Bones.” It was the poem’s overwhelmed recognition of the way things are, not its inspirational qualities, that so struck me and led me to share it back in that summer of 2016. Feeling so seen by a work of art is a potent experience, and I transformed that feeling into a kind of unalloyed hopefulness the poem doesn’t actually contain: My brain replaced the actual meaning of the poem with the buoyant feeling being seen gave me, which feels a lot like hope.

You write a poem thinking about what you’re trying to convey to some imaginary reader, not about everyone in the world including Meryl Streep somehow reading it, and for Smith it was entirely overwhelming watching her mentions fill up as actors, artists, and musicians posted the poem after the Pulse shooting and then again after the election in November. “Oh, I just read your poem on Charlotte Church’s Twitter,” a neighbor told her when they ran into each other on the street.

“The strangest thing about having a viral poem,” says Patricia Lockwood, “is that you are framed in reference to it afterwards to a degree that feels ensmallifying. It feels a little like you’re placed into a box.” Smith still grapples with the legacy of her viral poem. “Great,” she says resignedly. “What I’ll always be known for is writing this poem about how bad things are, and maybe they could be better, but they’re bad.” Her social media feed became a kind of “weird disaster barometer”: “Every time my mentions tick up, I know to check the news because something bad has happened.” Some readers ask her for a new poem of solace whenever there’s a fresh tragedy—“as if I’m some kind of literary first responder,” she says.

But what she appreciates, she says, is why people share the poem. “It makes them feel better somehow,” she says. “I think what they’re communicating is hope. Or at least a shared sense of collective mourning.”

After “Good Bones,” Smith’s profile rose fast. Suddenly offers were coming in: to read at festivals, to teach workshops, to get paid to be a public poet. She could make as much spending two days at a festival as she did editing five freelance projects. “You know,” she recalls, “I can change the way I make a living and have more time with my kids. But I realized, if I’m going to do this, I’m going to have to be braver than I am right now.” She hired a speaker’s agent, did interviews with newspapers and magazines, and started traveling more.

It didn’t go unnoticed in the insular poetry world. “Poets can be competitive,” says the poet Victoria Chang, a close friend of Smith’s. “There was a lot of pushback for her poem going viral. Even I was sort of catty about it at first.” The poet Devon Walker-Figueroa observed that the popularity of “Instapoets” like Rupi Kaur make it easy for writers to dismiss the work of someone whose poem gets screenshotted, turned into a JPEG, and shared on Twitter. “She’s been writing for years,” says Walker-Figueroa, “but she gets lumped in unfairly with people writing Hallmark dross, because of the way the poem gets distributed.”

And of course there’s good old-fashioned jealousy. “Frankly,” says the poet and critic Jordan Davis, “there are hundreds of people with teaching jobs who are publishing regularly and have multiple books—but they didn’t go viral, and she did.” He’s delighted about the success of “Good Bones,” he says. “Often, when a poet’s work spreads widely it’s a poem that doesn’t reflect what contemporary poetry can do. But ‘Good Bones’ really does. It’s a good poem.”

Smith’s new book, Keep Moving, emerged from a dark stretch in Smith’s personal life. It began with the realization that her marriage was unsalvageable. “Even when things were terrible, I always thought we could fix it,” she told me as we walked single file past a couple holding hands. “And had to, because we had a 9-year-old and a 5-year-old. Well, that didn’t happen.”

In October 2018, the decision had been made, but there was still a month before he was going to move out. “That was the worst time,” she said, “when you know it’s over but you’re having to cohabitate with someone you don’t like or trust or respect.” She stopped sleeping. She lost weight. “I was divorcing a litigator whose job it is to fight and win, who had resources that I didn’t have,” she said. “I was just honestly panicked.” Smith’s friend, the poet Ann Townsend, met her at a coffee shop to talk her through the practicalities of divorce. It was just dawning on Smith that she didn’t even know what all the bills the family paid were, so Townsend went through them: There’s the mortgage, there’s the water bill, there’s the gas bill … “OK,” Townsend said to her panicked friend. “We’re gonna make a list. We’re gonna figure it out.”

Aside from family and a few close friends, Smith didn’t yet feel comfortable sharing the specifics of her divorce with many people. Online, she revealed nothing, at first, to acknowledge “this huge tectonic shift that was going on in my life.” But she felt a gulf between her usual online persona—focused on poetry and supporting her writer friends—and the devastation she felt. “I wanted to be able to admit it,” she said. “You know, ‘I’m struggling, but I’m trying.’ ” She woke up one morning, made coffee, and tweeted her frustration and fear—with a hopeful spin:

“I was talking myself into it,” she said. “I needed to feel better so much.”

Within a few days, she was tweeting a “keep moving” message every morning, often from bed. She enjoyed the ritual. It gave her something to focus on besides her own anxiety. And the responses flooded in, just like with “Good Bones,” even though this time the only disaster was her own life. “People would say, like, ‘I’m exactly where you are now.’ ‘This is what’s going to get me through the next three hours.’ And just feeling like all of this terrible stuff that I was trying to process on my own was maybe useful to somebody else—that helped.”

She continued tweeting through the winter, her follower count growing—she now has over 60,000 Twitter followers—and while at a writers’ residency in Arizona, she wrote an essay about her divorce for the New York Times’ Modern Love column. Compared with the crystalline smallness of her poetry, an essay felt expansive, exciting—whole paragraphs waiting to be filled with her own story. A friend connected her to an agent, and she wrote a proposal for a book that would combine essays with the tweets, in a kind of hybrid of memoir and self-help.

“That isn’t what I do,” she said, laughing. “A self-help book? Come on. But people on Twitter and on Facebook and on Instagram were asking. ‘I would like to have these on a bedside table, you should make these a book.’ And I was about to be a single mom, who’s a poet, without a real job. I needed to pull myself out of this in some way.”

The agent sent the proposal out the day the Modern Love piece was published. Her Twitter feed became a warm bath, as her readers learned why it was that Smith was trying so hard to keep moving. Julia Cheiffetz, an editor at the Simon & Schuster imprint One Signal, said the book felt like an acknowledgment of the kind of hard times she’d been through too. “I’ve had cancer, I had an epically bad divorce,” Cheiffetz said. “I wished I had had this book when I needed it.” When the proposal sold, “it helped me sleep, honestly,” Smith says. “I didn’t even know how I was going to afford to pay my lawyer. And then I had this book.”

Though Smith is delighted that others find her tweets therapeutic, she describes them not as wisdom she’s imparting to others but as notes to self. “The you in all of them is me,” she says. With that in mind, you can read the dedication of Keep Moving as a sly wink or as a wholehearted embrace, for now, of her newfound ability to inspire readers. The dedication says, “For you.”

The book is a curious mix. Smith’s essays can be brutal in their honesty and sadness about her divorce, her miscarriages, and her postpartum depression. It’s in these essays that Smith exerts her superpower as a writer: her ability to find the perfect concrete metaphor for inchoate human emotions and explore it with empathy and honesty. She writes about the cones of the lodgepole pine, which only release their seeds when fire sweeps through the forest. She writes about kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken ceramics with gold-streaked lacquer, tying the craft cleverly to the work of recovering from sadness—honoring, not hiding, the things that happened to you. She tosses off perfect lines like they’re nothing, like this one about her daughter’s anxious questions: “I could almost hear her mind whirring, whirring, unable to shut itself down. I had an old MacBook that did that until it burned my lap.”

Meanwhile, the tweets, which appear in runs of five or six in between essay fragments, are doggedly positive, even as they acknowledge trauma. That’s a lot to pack into 280 characters, and Smith’s hairpin turns toward the light can sometimes make me grip the armrests:

Maybe you have a little voice inside that says you aren’t strong enough to handle what life’s left at your feet. That voice lies. Prove it wrong today—then repeat, repeat, repeat.

KEEP MOVING.

Even though so much seems to be in pieces, trust your wholeness. Accept that you cannot be sure of everything, but be sure of yourself.

KEEP MOVING.

Let go of the idea that things could have happened differently, as if this life is a Choose Your Own Adventure book and you simply turned to the wrong page. You did the best you could with what you knew—and felt—at the time. Now do better, knowing more.

KEEP MOVING.

The tweets are elegantly laid out, one per page, crisp black text in white text boxes, or white text on a soft gray background. Each “KEEP MOVING” is printed in a bolded sans-serif font at the bottom of the page. The book is designed by Oliver Munday, a witty and adventurous graphic artist whose work here is a little bit basic: Visually, the tweets resemble nothing so much as the inspo quotes that get shared widely on social media, the ones that say, like, “Be the energy you want to attract.” This impression of the tweets as visual wallpaper led me, while reading Keep Moving, to keep moving past the KEEP MOVINGs.

Smith stresses that the tweets are not poems, but other poets see connections between her online writing and her verse. “I think the tweets braid together very smoothly with what Maggie’s work does,” says Abdurraqib. “The tools she’s working with are really similar across genre. She has a command of language and an ability to get to the heart of direct address.”

“It gets very strange with the tweeting world, because we can’t decide what kind of writing it is,” Lockwood says. “There are things that you tweet that are worthwhile but they don’t feel like they have the heft of the work. It’s hard to figure out how to walk that line.” I know my knee-jerk distaste for the tweets and their role in the book is snobbish, a dismissal of self-help as different from, as Lockwood says, work—not a worthy accompaniment to the poems Maggie Smith has been writing for decades.

When I ask Davis, the critic, if there’s precedent for a poet sliding into self-help as a genre, he says, “The kind answer is, it really hasn’t been done well.” He chuckles, but then makes an argument on Smith’s behalf. “I think Maggie Smith’s book is explicitly an attempt to discuss this with herself. That she’s apprehensive about it speaks well to her chances at succeeding.”

I remind myself that writing these tweets, writing this book, is what Maggie Smith wants to do—what her readers have asked for. “She’s been called to action by her audience to offer advice and wisdom and perspective in these self-help tidbits,” says Walker-Figueroa. “And she’s answered that call.” And this is all aside from the fact, as Smith makes clear, that the book was necessary—necessary for her financial security, necessary for her emotional health.

“Your work can flow into the shape that people make for you,” Lockwood says. “Or you can try to break that shape.” I’ve come to think that with Keep Moving, Smith’s trying to do a little of both. What if the tweets aren’t simply filler? What if, instead, they’re more akin to the gold-flecked lacquer in kintsugi—holding a broken object together, gleaming in the light?

After our walk in the woods, Smith met me at her house, which was as she described it in Modern Love: periwinkle siding, just the one car in the driveway now that her husband’s is gone. The day had turned warm, and with her jacket off her short sleeves revealed the tattooed wild violets and lemon branches twisting around her upper arms.

Seeing the house, thinking of that Modern Love essay, which is as straightforwardly sad a piece of writing as Smith has ever produced—“like ‘Good Bones’ without the last three sentences,” she said—I wondered why her dominant emotional mode as a writer was sadness, not anger. Doesn’t she have plenty to be angry about? Don’t we all? “I’m as least as angry as I am sad,” she said. “But I’m much more comfortable being sad in public than I am being angry in public. I won’t say I can’t, I will say I can’t yet square that in my work.” She pointed out that what her children, any children, need in a difficult time is not a parent who’s consumed by anger. “So every time I want to kick a wall, instead I do something that’s out of care for them.”

I get that, I said, transmuting anger into care. But what about transmuting anger into action? Good art doesn’t always need to meet the political moment, but what about this moment? What worried me about a writer like Smith retreating into self-help right now, I said, was that to focus on taking care of yourself and your family emotionally might be exactly what we don’t need art to be telling us as the world falls apart.

“In some ways,” Smith finally said, “I think care is action. It’s a kind of action. And I don’t mean that in like a Pollyanna way, like we can just love each other and heal everybody. But I do think a lot of problems we’re facing stem from the fact that we are not thinking about others as ourselves.”

I mentioned a phrase Smith uses several times in her tweets: “Do something today, however small … ” Often the prescribed action is directed not only inward, but outward: “Do something today, however small, to light up your own life. Or shine on someone else—the light will reach you, too.” In my copy of Keep Moving, next to that tweet, I’d written “oh brother,” but I was trying to shake away my cynicism and really think about what such a thing would look like. I asked her, “Is that care as action?”

Smith smiled. She mentioned, not for the first time, the friends who had helped her through her divorce, the casseroles left on her porch, the phone calls late into the night. “But it’s not only that,” she said. “Sometimes we talk about words and actions as being separate. But I don’t know … when I tweet a response to your tweet that says, hey, you know, you’re not in this by yourself—that’s an action.”

While I was on the flight home, Smith tweeted another aphorism, not from herself, but from the writer Grace Paley: “The only recognizable feature of hope is action.” Part of me was annoyed to have our impassioned discussion boiled down to an inspirational quote on Twitter. But I scrolled through the responses—“These are the words I didn’t know I needed to hear,” “Love this,” “Hope made me drive my absentee ballot 30 miles to deliver it in person”—and calmed down a little.

That evening I sat on the porch of my own house, thinking about the end of “Good Bones.” The smoke in the upper atmosphere made the sky a gorgeous, shocking orange—a “beauty emergency,” as Smith calls such moments where you just have to drop what you’re doing and look. Smith had mentioned that the reason she thought the poem wasn’t a downer, as some on the internet declared, was that its final lines were a call to action of sorts. “It’s not super direct,” she said, “but it’s there.”

I pulled the poem up on my laptop, that neat little JPEG shared hundreds of thousands of times. If the world is like a house with good bones, the question is, how are we to make things better? It’s not by concealing what’s bad about it, despite what the poem’s speaker hides from her children. It’s by treating the world like we’d treat that house: by tearing it down to the studs and building something new from that skeleton. We might not feel like there’s a lot to work with right now, in our burning world. But we could still make this place beautiful.